- Home

- Share Prices

- AQSE Share Prices

- Euronext

- Stock Screeners

- Share Chat

- FX

- News & RNS

- Events

- Media

- Trading Brokers

- Finance Tools

- Members

Latest Share Chat

Political and Financial Market drama continues apace

Monday, 17th October 2022 11:39 - by David Harbage

Media headlines are currently dominated by financial markets and domestic politics, with the average ‘person on the street’ struggling to understand the dynamics of the former and bemused by the personnel cum fiscal policy changes in the political sphere. Investors and traders will be looking to 31 October when new Chancellor Jeremy Hunt is due to provide a further financial statement – featuring the Office of Budgetary Responsibility’s (OBR) forecasts on public funds and further guidance on Government policy. In the meantime that perennial headwind for market progress – uncertainty – is set to continue, at pace.

Gyrations in the government bond, colloquially known as gilt, markets (essentially longer term interest rates applicable to public debt, which is priced on a daily basis, reflecting supply-demand drivers as well as confidence in the reliability of governments to service – pay income coupons and redeem - such financial obligations) have unsettled investing institutions, notably UK pension funds. The perennial focus of the politically-independent Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is on the pace of the UK’s inflation (targeted to rise by circa 2% per annum). This is controlled by setting of interest rates and, to a lesser extent, the money supply via the purchase or disposal of bonds - known as quantitative easing or tightening (QE/QT).

Beyond an assessment of whether an investor is receiving a satisfactory or beneficial real (after inflation) return from gilts, a less frequent cause for financial regulators’ concern surrounds the confidence that investors can have in the reliable operation (the sustainability, if you wish) of the workings of the bond markets. Beyond the pace of economic activity (typically measured by annual growth in gross domestic product, GDP), one of the prime considerations when determining a country’s financial health would include an assessment of the total amount of debt (in the UK this would extend beyond the government bond market to include National Savings and other obligations to corporate institutions), when it matures and the cost of servicing that debt. As regards the latter, while much is known (via coupon income being at a fixed rate), a growing proportion has been linked to the rate of domestic inflation – which, of late, has become much more expensive to service. Clearly the pick-up in inflation, much of which is imported (and, therefore in the UK, accelerated by weakness in sterling) has an adverse impact on public finances.

Along with slowing economic performance, such a prospect reduces investor confidence in UK gilts, which has led to their credit worthiness being reduced (Britain had the highest possible triple AAA rating from 1978-2016, it was reduced to AA after the Brexit vote, but credit rating agencies Standard & Poor’s and Fitch lowered their outlook to “negative” following last month’s ‘mini budget’ citing the large and unfunded fiscal package which could lead to a significant increase in fiscal deficits (HMG’s current account of revenue & expenditure) over the medium term. A higher credit rating – be it a government or corporate issuer – means that investors will accept a lower return; conversely, a bond issued with a lower rating has to offer a higher reward so, in the case of gilt issuance a higher coupon which costs the Treasury (the government’s finance department) more to service.

Having been challenged by some readers on the assertion that geo-political uncertainties remain the biggest hurdle to a restoration in confidence in financial markets or risk assets, it might be helpful to ‘flesh out’ some of the considerations that investors – be they institutional or private individuals – currently face. Before doing so, it might be helpful to suggest that a global perspective, rather than a local one, should dominate investor thinking – given that many macro-economic influences (such as interest rates and inflation), as well as less tangible ones (such as consumer, business or investor confidence) travel rapidly in an interconnected world. While a ‘bottom-up’ perspective (looking at an individual investment on its own merits) remains a respectable means of assessing an asset, global or wider influences should never be ignored.

A list of considerations or risks for an investor’s perusal - which might impact in this decade, and the next, could be endless but might include:

1. Geo-politics - features war (historically, the cause of greatest inflation, public indebtedness, loss of human and other resource, destruction of production), alongside such other demographic or other themes such as the prospect of a reversal of productivity-enhancing globalisation. Nations are set to become more independent as they seek resilient sources of vital product, from energy to medical supplies. Beyond Russia’s incursion into Ukraine, China’s claim on the sovereignty of Taiwan is another concern with the US promising to defend the small East Asian country.

2. Health – the Covid pandemic almost certainly had a much greater adverse financial impact than its 1918 predecessor Spanish flu. In particular, the extended (beyond discovery of an efficacious vaccine) economic lockdown, diversion of resources and government financial support was equivalent to a major war.

3. Monetary policy – in response to inflation - ranges from being complacent (slow to act, which could lead to a deeper, more protracted economic downturn) or being hawkish in hiking too aggressively (‘throwing baby out with bath water’, ignoring the delayed impact effect of rate hikes) thereby unnecessarily destroying businesses, jobs.

4. Local politics – rise of ‘divided nation’ in terms of strategies, includes debates on the redistribution or expansion of wealth

5. Pace of change, short termism - features government policy & media-influenced U turns, which discourages corporate investment; also applies in financial markets, notably via more complex geared instruments, such as recently publicised liability-driven investment (LDI) in pension schemes.

6. Other global issues, such as Climate change – government-driven measures, often dislocating the status quo, are expensive and inflationary.

7. Other local issues, such as a tight labour market (may ease as early Covid-induced retirees return to the workplace, via robotic technology, immigration).

8. Corporate headwinds: accountability, rules & regulation, litigation expense. Higher interest costs on debt is unlikely to be a major expense, as most reasonable sized firms have fixed the rate of interest they pay on their debt.

The above is likely to equate to slower global economic growth, with reduced consumer discretionary spend - albeit to the historic essentials of shelter & food, can be added a long list beginning with the mobile phone – and an inexorable rise in debt, public and personal in the short term.

In response to the above, the reader might surmise that investment in stock market assets (such as gilts, company bonds or shares) represents an unpalatable risk. However, everything is relative - as Albert Einstein might have said – and one has to consider the risks and rewards inherent in each asset class. To, figuratively speaking, “Do nothing”, and leave monies in a bank or building society account earning a sub-inflation return is to destroy the real (purchasing power, as higher prices impact) worth of your liquid wealth. Inflation, it should also be remembered, has the effect of reducing debt in absolute terms as well as increasing revenue, profits and dividends of companies or property assets.

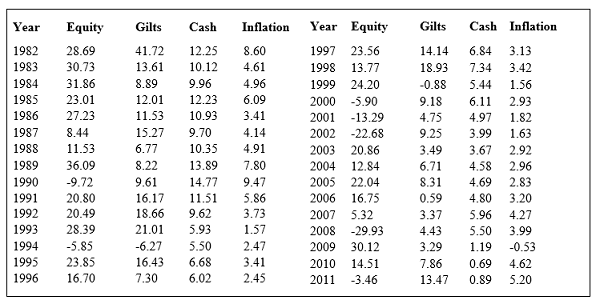

History shows how different asset classes have performed, covering times of both high, negligible and negative economic growth, various paces of inflation, wars, geo-political tensions, pandemics, health scares, oil and other supply shortages. While rather dated now, the annual returns on different assets – taken from one of the writer’s earliest blogs – evidences the volatility, which intuitively one might expect. According to one’s appetite for risk (both of those mentioned above and other, more personal concerns) and anticipated future liabilities (from large expense to normal household expenditure), so a prudent, long term decision of appropriate asset allocation can be taken – ideally regularly reviewed in conjunction with a financial or other professional advisor.

The UK Equity returns are based on the FTSE UK All Share Total Return index UK Bond returns are based on an equally weighted mix of the FTSE British Government Fixed All Stocks Total Return index and the Barclays Capital £ Aggregate Bond Total Return index, Cash returns are based on 3 month London Interbank Offer rate (LIBOR) and Inflation is based on the UK Retail Price index (RPI). Source: Thomson Datastream.

For ease of reference and reiteration of the writer’s current views, excerpts from the previous article, “Beware saying the market’s wrong” published on 26 September 2022 is shown below:

Financial markets experienced a turbulent, bruising end to September as central banks took action to counter uncomfortably high inflation, by raising overnight interest rates in Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States – which has increased the prospect of recession in Europe and North America. Looking back on this year’s two previous commentaries “Batten down the hatches” in March and July’s “The darkest hour is just before the dawn”, the writer retains the same cautious perspective on the short-term outlook.

- A view on Financial Markets: "The darkest hour is just before the dawn"

Journalists would rightfully say that there has been a plethora of significant news events - both geo-political and economic – to impact financial assets and, in the modern age of ever-faster transmission and rise in distribution channels (notably web-based social ones, increasing the prospect of misinformation), the media’s has become increasingly characterised by ‘drama’ and ‘noise’. Newcomers to stock market investment ask if the past couple of years’ roller coaster performance from company shares represents the norm and, while one can point to exceptional events like the Covid virus or Russia’s incursion into Ukraine, investors have always had significant risks to contend with. Different events do, of course, present risks of varying nature and magnitude, but the media’s volume seems to have risen – certainly to the point of drowning out advice of positive tailwinds. Private ‘Do-It-Yourself’ investors must always take a balanced longer term view of their circumstances, needs and maintain an emotionally detached perspective on the relative merits and risks attached to their investable universe of assets.

So what has changed in the past three months, and how has that impacted the author’s view and suggestions made earlier this year to a potential investor? Russia’s lack of military success in the Ukraine has prompted President Putin to call up another 300,000 soldiers and talk of using nuclear weapons to ‘defend’ his country. Clearly, the Russian leader is unwilling to ‘lose face’ or seek peace – despite growing internal protest – and railing against the West’s economic sanctions, with Europe having to search for new sources of increasingly expensive gas and oil this winter. Meanwhile, wider global political tensions have risen as US President Biden promised to defend Taiwan from any predatory action from near neighbour China.

Against such geo-political headwinds, the global macro-economic landscape has deteriorated: the historical strength of the greenback in times of international concern (the US dollar has appreciated by 20% against the euro, sterling and yen in 2022 to date) has contributed to supply-constrained inflation accelerating in most corners of the world. With economists’ forecasts of consumer price indices struggling to keep up with announced CPI (currently 8.2% in the US, 10% in the Eurozone and 8.6% in the UK), central banks hiked rates in September. The Federal Reserve Bank has been most hawkish, increasing rates by 0.75% to 3-3.25%, the European Central Bank also hiked rates by 75 basis points to 1.25% earlier in September and the Bank of England moved its Bank rate 0.5% higher to 2.25%. These moves took financial markets by surprise, and the bond (fixed income, reflecting longer term interest rates) market – which has often be a more reliable portend of economic prognosis than equity valuations – shook off its early August complacency to reflect a more negative outlook.

Ex-Chancellor Kwarteng’s package of fiscal announcements spooked financial markets which took the view that the burgeoning public debt (the misnomer ‘mini budget’ added £200bn) represented an unacceptably high burden - becoming more expensive to service, via higher yielding (fixed or inflation-linked) government bond issuance. The prospect of reduced confidence in the UK’s economic performance (the Bank of England indicated that Britain was experiencing recession, by reference to the technical definition of two consequent quarters of negative growth) and its public finances caused sterling to fall further, exacerbated by calls for a 1% emergency hike in Bank rate to stabilise the currency. The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee is next formally due to meet on 3 November.

The overall strategy –flagged by Ms Liz Truss in her party’s leadership debates – of a ‘Pro-growth via lower tax & regulation’ would have received a warmer welcome at a time when economic growth was more obvious (for example when the Conservative party gained a large majority in December 2019’s general election). However much ‘water has passed under the bridge’ since then and the current squeeze on domestic living standards could make this package of financial measures a risky political move. Investors will have to hope that “fortune follows the brave” but, notwithstanding the exceptional short term support given to consumers and business to counter higher energy costs, this winter looks like a particularly difficult one.

As mentioned previously, history shows that stock market investments perform best at the bottom of an economic cycle – when interest rates are cut to stimulate activity and investors look forward to an improvement in company profits – but few commentators believe that the nadir is in sight, with the political landscape (likened to a return in the ‘Cold War’) remaining problematic at best and opaque.

Turning to equity valuations, both of companies listed on recognised stock markets and in the private arena, most commentators suggest that they already discount much bad news and so some investors might be tempted to ‘test, if not re-enter, the water’. They currently would represent a minority, (based on the estimated weight of monies that has exited the European, UK and US stock markets over the summer months), and whether such institutions or individuals prove to be astute, early or just plain wrong will primarily depend on any military escalation or easing in tensions. While the immediate economic picture is dramatic and gloomy, one can envisage a more stable scenario (of lower rates & prices increases, albeit offset by rising unemployment) emerging in 2024.

Pressed for a view of suggested action for individuals taking the appropriate longer term view (essentially consider the foreseeable future, but typically with a minimum of five years, as a sensible time horizon), we would reiterate many previously expressed views or general principles of long term savings. Although negligible returns are paid on savings accounts (which have barely risen in response to the hikes in Bank rate), it makes sense to retain cash reserves for unexpected needs, to drip-feed monies into the market (perhaps via monthly savings plans) or to take advantage of opportunities to purchase undervalued assets – mindful that fearful or enforced selling (on the part of traders or investors with shorter time horizons or liabilities) might take prices lower than perceived fair value.

On the ‘home front’ a new Prime Minister and Cabinet have made noises about returning the UK to a path of higher productivity and growth, via a smaller public sector featuring a reduction in personal and corporate taxation. A slowdown in economic activity caused by a squeeze on personal consumption (notably as higher energy prices impact) might have persuaded the Bank of England to look beyond current high inflation and adopt a more dovish strategy. However, headline data – the consumer price index may have peaked at 10.1% in August – remains a real concern, against a backdrop of an increase in wage demands and industrial action by the labour force (as the UK has more unfilled vacancies than unemployed).

It is worth reiterating that real assets, be they land, minerals in the ground, property and business are the intuitive beneficiaries of higher prices and, even as interest rates are rising, the offer on cash in real terms can become even more negative (as inflation is running ahead of deposit rates). By contrast with bank or building societies’ unappealing offering (as interest paid on savings accounts extend their lag on Bank rate), the potential for growth in dividends or rental income suggests that investment in corporate stocks or real estate is likely to retain their relative attraction as a source of immediate income and growth in such income.

While speculators and traders may have a different view, most institutional and retail stock market investors with an appropriate longer term perspective will be mindful of income returns and view turbulence in company share or bond prices as a secondary consideration. A prudent investor will want to maintain a broad spread of equity investment – featuring various types of asset, seeking to minimise losses from any individual security, via a diversified portfolio – and always making decisions based on a medium or longer term perspective. This necessitates ‘weathering stormy conditions‘, that can cause good quality investments to be temporarily mispriced, and to resist the temptation of capturing every twist or turn in market sentiment or theme, which could prove to be transitory and pose the perennial problem of when to repurchase an asset you wish to own for the long term. The adage “time in the market is more critical than timing the market” best sums up the need to be a patient owner, rather than a trader, of company shares – especially if the prime rationale for taking a stake in successful businesses is to benefit from higher profits, dividend income and asset appreciation.

Upon seeing any glimmer of resolution in the current dark geo-political situation, the bold investor might decide to utilise the cash which has accumulated to add equity or property investments which appear to be most underappreciated by the market. In particular, weak investor sentiment has meant that the share prices of a number of investment trusts have fallen further than one might expect (a) because the underlying asset prices have retreated and (b) the share price has fallen further than the wider market, which has reduced the premium rating or increased the difference (known as the discount) between a trust’s share price and the underlying value of its assets. The institutional or astute private investor will be aware of the normal or average discount over say a one or two year period and, when the discount has significantly widened from this historical ‘rating’, will endeavour to finesse existing positions by adding at opportune moments.

Over the past three months or so, almost all risk assets have delivered disappointing returns despite often encouraging corporate trading results and upbeat management statements. Smaller and medium sized firms, which often offer the prospect of higher future growth than the largest businesses, have been particularly neglected by global institutions – many of whom possess negative views on the British economy. By contrast, the FTSE100 index’s multinationals retained their recent relative appeal, aided by the translation effect of overseas profits (boosted when considered in sterling terms) and an intuitive belief that larger companies can survive an economic downturn better than smaller listed or private family-run firms. However, such potential ‘silver lining from recessionary clouds’ – potentially from an increase in market share as ‘Momma-Poppa’ businesses fail, perhaps acquiring their assets at fire-sale prices – extends beyond the UK’s largest hundred listed concerns (the constituents of the FTSE100 index) to medium and smaller sized quoted companies, which may also be industry leaders.

Looking forward, events in the Ukraine dominate and undoubtedly represent an adverse sea change for the world: a return to the 1980s’ relationship between autocratic and democratic nations. China represents something of an enigmatic factor: being closer to Russia in political terms, but dependent on US & European demand for its manufactured product. A cessation of hostilities in the Ukraine will not necessarily facilitate an immediate return to the pre-invasion ‘landscape’. In addition to increasing spend on defence budgets, the Eurozone will seek to reduce dependence on Russian oil & gas and, post the Covid experience of supply shortages, most developed nations will endeavour to become less dependent on others for essential product.

Reiterating a belief in successful company businesses and property investments for the appropriate longer term but, anticipating tougher economic conditions and geo-political uncertainty (at home and abroad) over coming months, it remains sensible to exercise caution in the short term. Further to the suggested asset mix and investment selections proffered in this blog’s previous “Batten down the hatches” and “I’m taking early retirement – how should I invest £100,000?” articles, the author would maintain the maximum allowed in Premium Savings bonds of £50,000 as a cash reserve. Beyond that, the following investment trusts offer long term appeal but, please note, these are not personal recommendations - readers must carry out their own research):

UK listed company shares - both large and smaller listed companies - via Aberdeen Equity Income (AEI) (on an 11% discount to its underlying asset valuation as at 14 October, offering an income yield of 7.4%) and Henderson Opportunities (HOT) (on a 16% discount to its NAV, with a 3% income yield).

Private company shares - via Harbourvest Global Private Equity (HVPE) (on a 47% discount to its 31 August 2022 valuation), ICG Enterprise (ICGT) (on a 45% discount to 30 July worth) and Pantheon International (PIN) (on a 51% discount to 31 August NAV), Real estate - via Schroder Real Estate (SREI) (on a 46% discount to NAV), Civitas Social Housing (CSH) (on a 47% discount), Aberdeen Property Income (API) (on a 52% discount) and UK Commercial Property (UKCM) (on a 51% discount). All of these property trusts are based on their last published, 30 June 2022, quarterly valuations.

The Writer's views are their own, not a representation of London South East's. No advice is inferred or given. If you require financial advice, please seek an Independent Financial Adviser.